Program

Tux & Tom Productions and Spark and Echo Arts present

A Little East of Jordan

[The Geography of Healing]

Directed/Choreographed

by Patrice Miller

Featuring:

Laura Hartle, Stephanie Willing,

Morgan Zipf-Meister

The text was created in a collaboration between the performers,

Patrice Miller, and those who submitted their stories to the project.

This piece is dedicated wonder-worker Kelly Coviello

————————————————————————————

A Little East of Jordan is a performance in six parts.

Part One: Intention

This is a piece about healing.

Think about your healing,

think about your body, your home, your country,

and how you would live in it if your were healed.

Part Two: Themes on a Variaton [The Sands]

Stephanie Willing

Part Three: Ritual

Laura Hartle, Stephanie Willing, Morgan Zipf-Meister

Part Four: Process

Part Five: Performance: The Sands; The Mountain

Part Six: Exit

Program Notes:

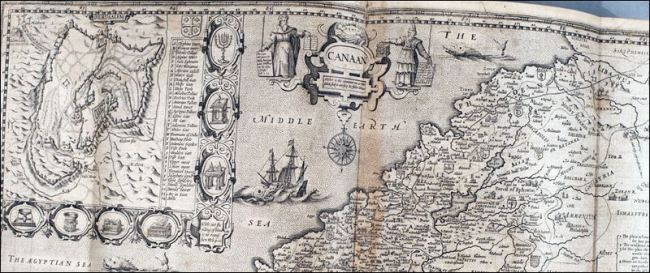

Commissioned by Spark and Echo Arts, A Little East of Jordan (The Geography of Healing) is inspired by the first works of wonder-worker Elisha, and uses theater, dance, crowd-sourced text, and anthropology to explore the dialogue between our bodies, minds, and space as we consciously undergo change.

2 Kings 2:21-25: “And he went forth unto the spring of the waters, and cast the salt in there, and said, Thus saith the Lord, I have healed these waters, there shall not be from thence any more death or barren (land)” So the waters were healed unto this day, according to the saying of Elisha which he spake.

And he went up from thence unto Bethel: and as he was going up by the way, there came forth little children out of the city, and mocked him, and said unto him, Go up, thou bald head; go up, thou bald head. And he turned back, and looked on them, and cursed them in the name of the Lord. And there came forth two she bears out of the wood, and tare forty and two children of them.

And he went from thence to mount Carmel, and from thence he returned to Samaria.

A Little East of Jordan is the first line of an Emily Dickinson poem.

Directors Note:

When Lauren Ferebee approached me about this project, I took the opportunity to challenge myself as a performance maker. Instead of writing alone or seeking a playwright, I opened up the text-creation to a number of people, resulting in a rich diversity of stories and responses. Instead of rehearsing for five days a week for three or four weeks at a time, we performed pieces of this throughout out the year. Instead of giving you a program to rustle through pre-show, I gave you an intention, some salt, and water.

I also documented my process in a more precise manner than usual. What I noticed is that it is very hard to create material that feels personal when there are large political happenings constantly streaming across your computer screen, your phone, your eyes in Times Square. And I remembered that the political is personal. That nothing happens in a vacuum. With this in mind, Laura, Stephanie, Morgan and I wove together various pieces to create an honest account of attempting to create when you feel situated in the midst of chaos, of attempting to heal yourself when the world insists on never easing up on you.

Program Bios:

Stephanie Willing is an actor-dancer-writer who loves to do all those things at once. So thanks to Patrice for making that happen in this piece. Stephanie is a NYTE 2014 Theater Person of the Year. Love to Matthew and the kitties.

Tux & Tom Productions is a fiscally-sponsored project under Fractured Atlas. We couldn’t create without the support of our wonderful donors.

Special Thanks:

Concrete Timbre & Two Moons Cafe, The International Women Artists’ Salon, Lauren Ferebee, Emily Zempel Roberts, Jonathon Roberts, Chris Chappell, Standard Toykraft, wonderful donors, and all of those who submitted their stories to us.